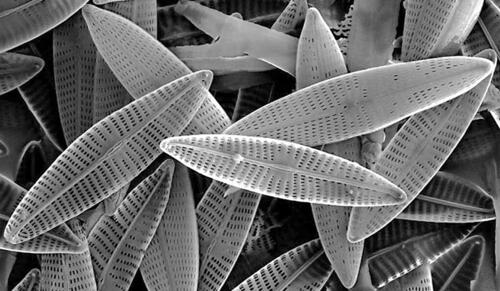

Diatoms — tiny phytoplankton that are responsible for a fifth of all energy converted into matter by plants — may have become important much earlier in the development of Earth’s ocean ecosystems and carbon cycle than previously thought, according to a new Yale study.

In fact, much of what scientists knew about the rise of diatoms might be inaccurate.

“Our results are critical for understanding everything from the rise of whales to the carbon cycle,” said senior author Pincelli Hull, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. “Diatoms are responsible for a large segment of the primary productivity on the planet and were thought to have become prominent only relatively recently.”

Sophie Westacott, a doctoral student at Yale, is lead author of the study, which appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Co-authors of the study are Noah Planavsky, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences, and Ming-Yu Zhao, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Diatoms were thought to have grown progressively more abundant from the start of the Cenozoic Era, 66 million years ago, until today, Westacott said. The prevailing view was that the rise of diatoms was particularly rapid in the past 20 million years — which coincided with a surge in the diversity of baleen whales and the abundance of terrestrial grasses.

“One hypothesis was that the increased dominance of diatoms led to the rise in baleen whales,” Westacott said. “Another hypothesis was that since grasses contain a good deal of small silica particles, and diatoms make their tiny shells out of silica, then perhaps grasses also contributed to the abundance of diatoms by putting more bioavailable silica into the ocean.”

The increase in diatoms also has been linked to the decline in atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the past 40 million years, sea level change, and the restructuring of ocean ecosystems.

These theories were based on evidence of diatoms in the fossil record. But according to the new Yale study, diatoms may have been abundant much earlier — they just weren’t being preserved.

The Yale researchers used numerical models to predict what happens to diatoms when they are buried beneath sediment that drops down onto the seafloor. Data for the model included estimates of sea water temperatures near the seafloor and sedimentation rates for the past 66 million years.

“From this we found that a diatom is much more likely to be preserved in today’s ocean than in the deep past, say prior to 20 million years ago,” Westacott said.

The findings suggest that diatom proliferation is not tied to either grassland development or whale evolution, but rather that all three were driven by a gradually cooling climate. This has important implications for understanding ocean ecosystems and the global carbon cycle over the last 66 million years, the researchers said.

by Jim Shelton