A Yale-led study turns up the heat on a key question about dinosaurs’ body temperature: Were they warm-blooded or cold-blooded?

According to a new technique that analyzes the chemistry of dinosaur eggshells, the answer is warm.

“Dinosaurs sit at an evolutionary point between birds, which are warm-blooded, and reptiles, which are cold-blooded. Our results suggest that all major groups of dinosaurs had warmer body temperatures than their environment,” said Robin Dawson, who conducted the research while she was a doctoral student in geology and geophysics at Yale.

Dawson, now a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, is lead author of a new study in the journal Science Advances. Yale paleontologist Pincelli Hull is a co-author of the study, as are former Yale researchers Daniel Field and Hagit Affek. Hull and Affek were Dawson’s advisors at Yale.

The researchers tested eggshell fossils representing three major dinosaur groups, including ones more closely related to birds and more distantly related to birds.

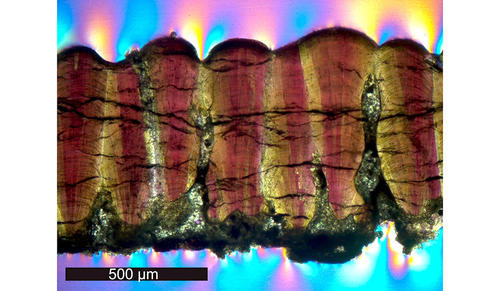

The testing process is called clumped isotope paleothermometry. It is based on the fact that the ordering of oxygen and carbon atoms in a fossil eggshell are determined by temperature. Once you know the ordering of those atoms, the researchers said, you can calculate the mother dinosaur’s internal body temperature.

For example, eggshells of a Troodon, a small, meat-eating theropod, tested at 38 degrees, 27 degrees, and 28 degrees Celsius (or 100.4, 80.6, and 82.4 degrees Fahrenheit). Eggshells from the large, duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura yielded a temperature of 44 degrees Celsius (111.2 degrees Fahrenheit). Both the Troodon and Maiasaura eggshells were from Alberta, Canada. Meanwhile, fossilized dinosaur eggs from the oospecies (a species classification limited to dinosaur eggs)Megaloolithus, from Romania, tested at 36 degrees Celsius (96.8 degrees Fahrenheit).

The researchers conducted the same analysis on cold-blooded invertebrate shells in the same locations as the dinosaur eggshells. This helped the researchers determine the temperature of the local environment — and whether dinosaur body temperatures were higher or lower.

Dawson said the Troodon samples were as much as 10C degrees (50 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than their environment, the Maiasaura samples were 15C degrees warmer (59 degrees Fahrenheit), and the Megaloolithus samples were 3-6C degrees (37.4-42.8 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

“What we found indicates that the ability to metabolically raise their temperatures above the environment was an early, evolved trait for dinosaurs,” Dawson said.

The findings may have other implications, as well, according to the researchers. For example, the study shows that a dinosaur’s body size and growth rate is not necessarily a good indicator of body temperature. The researchers further said their findings might add to the ongoing discussion about the role of feathers in early bird evolution.

“It’s possible that dense feathers were primarily selected for insulation, as body size decreased in theropod dinosaurs on the evolutionary pathway to modern birds,” Dawson said. “Feathers could have then later been co-opted for sexual display or flying.”

Support for the research came from Yale, the Isaac Newton Trust and U.K. Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship, the Sloan Research Fellowship, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant, and the Israel Science Foundation.